Nostalghia by Andrei Tarkovsky: Reconfiguring Nostalgia Through Representational Aesthetics

Note: This post has an audio-visual recording on loop at the bottom and can be unmuted or/and paused manually.

Nostalghia (1983) by Andrei Tarkovsky

Watching any of Andrei Tarkovsky’s films is a form of prolonged meditation. Every Tarkovsky film that I have watched has always left me in deeply introspective reveries while slowly growing on me, with the exception of Mirror and Stalker which left indelible imprints on me as soon as I finished watching them. I think it is Tarkovsky’s uncanny ability to make me continually revisit and replay certain scenes in his films that truly makes him the greatest in my eyes. Nostalghia (1983) was no different.

I decided to watch this film because a friend in Andorra had very recently watched it and sent me a small video recording of an incredibly shot sequence accompanied by a superb monophonic sound design. However, as with every Tarkovsky film, I had to take a couple of days to mentally prepare myself to sit down and watch it in one sitting. I cannot eat when I watch his cinema. Not because I choose not to, but rather because his films are so arresting in nature that I have no choice at all in this matter. Once I finished Nostalghia, I had to simmer in my thoughts for a couple of more days until the disorientation of watching it wore off as I slowly absorbed enough to write this review.

I can understand why a lot of cinephiles would recommend Nostalghia as a starting point for anyone who is interested in understanding Tarkovsky’s cinematic oeuvre. It is, after all, the only non-Russian film that he made outside of the Soviet Union. Unlike most of his other films, this film has a discernable plot, at least in the beginning. A Russian poet is on an intellectual journey to unearth the life of a deceased Russian composer Pavel Soznovsky who had visited Italy in the 17th century before returning to Russia and drinking himself to death. It seems simple and straightforward enough but viewers are thrown off-guard right from the moment the film begins with a car stopping in the middle of a misty meadow as a woman who happens to be a translator (Domiziana Giordano) gets off to make her way to a church at the behest of the protagonist Andrei (Oleg Yankovsky). There are Christian overtones that very quickly define the purpose of a woman but this trope is only sparingly brought up in the rest of the film.

Andrei is already quite tired of the lush beauty of Italy which is so different from the desolate landscapes of Russia but this is not translated in the visual sequences of the film. On the contrary, the viewers are left confused about whether the protagonist and his translator are really in Italy or in Russia. This is the genius of Tarkovsky. He deftly creates a sense of confusion in the very first minute of the film. Tarkovsky had deliberately chosen to shoot in a small area of Tuscany for its resemblance to the countryside that surrounded Moscow. The theme of nostalgia has already aesthetically permeated through this carefully crafted mise-en-scene.

Andrei is unable to forget the uncultivated countryside of Russia where his wife and family await his return while his translator Eugenia recites a poem by Arsenii Tarkovsky (Andrei Tarkovsky’s father) in Italian only to be told by Andrei that the true meaning of the poem is lost in translation and that art cannot be translated. The short discourse is an intellectual one wherein Eugenia challenges this break by mentioning that music needs no translation and can be felt without words. The theme of untranslatability is now planted in the narrative along with the cultural clashes that happen within the realm of translation. Eugenia and Andrei do not get along well. In my understanding, this scene was Tarkovsky’s oblique attempt at trying to showcase the difficulties of a Western audience trying to understand Russian sensibilities and also a means of depicting how they perceived his films.

As the film progresses, viewers witness that Tarkovsky introduces a madman by the name of Domenico (Erland Josephson), who becomes a subject of great interest for Andrei the protagonist. Domenico and Eugenia undergo a disconnect almost as soon as the latter tries to pry information out of him at the request of her client. She leaves the scene which moves on to Andrei striking up a conversation with Domenico as the latter cycles relentlessly on a broken, stationary bicycle. After successfully befriending Domenico, Tarkovsky challenges the theme of untranslatability by bridging the gap between the insane and the sane. Andrei is invited into Domenico’s abode and this is where memories of the sane and the insane begin to mingle with reality.

Tarkovsky uses two distinct palettes to showcase two narratives that interweave and propel the film to the end. One is the etiolated color palette that primarily comprises hues of brown and green, and the other is an austere palette of silver and gray that denote nostalgic flashbacks. The choice of colors is deliberate, greens and browns represent earthiness or the materiality of reality, whereas the silver and grays represent ethereality. The etiolation is once again a deliberate choice, which in my understanding, was made to chromatically indicate how Andrei is unable to truly experience his lived reality in Italy.

However, the true potential of these two narratives and color palettes is achieved only through their repeated intercuts. Andrei is unable to commit to his research as he continually longs for his family and has flashbacks of Russia. His nostalgia is not a romanticized, easily assimilable, and palatable past memory that the postmodernists fondly theorize about. It is a deeper, more serious, and continual longing that is impossible to fulfill because it is more imagination than past reality. And thus, it acquires a debilitating quality that slows down and stalls Andrei from returning home.

One would ask, how does Tarkovsky show such a complex, avant-garde reconfiguring of nostalgia? The idea of nostalgia becomes precisely the locus of most of Tarkovsky’s characteristic cinematic devices that function as visual correlatives of complex emotion that exteriorize the inner experience of the characters in the film. He deploys the same slow tracking camera movements that he had used in Stalker while offering the viewers very similar painterly shots of nature and Yankovsky to push them into psychological excursions. The medieval architecture in slow decay and ruin with moss and foliage growing as puddles glisten in the misty light of the day, are visual indicators of the fallibility and porousness of human memory that transforms into nostalgia with time and separation. Nostalghia, much like his other films, urges the viewers to engage with the interiority of the protagonist as he dreams and while he dreams, his mind melds reality with it, thus rejecting the modernist desire for teleological progression. By focusing on the extended mind-states and flashbacks of both Andrei and Domenico, Tarkovsky not only rejects the Soviet Socialist film style of representing daily, objective realities of propaganda films sanctioned by the state, he also fights against the passive, brain-dead mass appeal of cinema that Walter Benjamin warned the world about in his seminal essay “Work of Art in the Mechanical Age of Reproduction”.

Tarkovsky continually resists the surface model or simulacra and escapism of modern cinema by pushing his depth model of cinema and subsequently challenging the “pastiche” of postmodernism that solely relies on a consumption of the past that is bereft of the viewers’ lived experience. Tarkovsky uses a deconstructionist approach to portray the erosion of deep, meaningful engagement and experience through his increasingly tortured protagonist who slowly but surely loses his agency with respect to carrying out his research. Andrei no longer simply remembers the past. His “nostalgia” is the past that is embellished by his imagination, and imagination as we know it is never lived in reality because if it were, then it would cease to be what it is. The more he familiarizes himself with the memories of Domenico, the more caged he is in his self-sustaining bubble of nostalgia. The camera takes become ever so slow at this point. Viewers truly sink into these delirious reveries of both Domenico and Andrei and this is where the intercutting of flashbacks merges the seemingly insurmountable bridge of untranslatability of culture, language, space, the past, and the present. The moment of their complete merge is crystallized when Andrei sees Domenico instead of his reflection in a mirror. Andrei is no longer completely sane and his longing can no longer be rationalized. At the same time, we notice in the subsequent mise-en-scenes that the puddles increase in number, and Domenico’s abode slowly overflows with water.

Water is a recurring symbolist imagery in Tarkovsky’s works. It is almost always Tarkovsky’s symbol of memory but in Nostalghia it denotes nostalgia as well as depression. Andrei keeps taking pills and even undergoes an episode of nose-bleeding due to his medication and as the film progresses, the waters rise, and his depression proportionally deepens. There is more stasis and more silence in Tarkovsky’s long shots as they function as forms of free indirect discourse created by the understanding and reception of the scenes by the individual viewer.

Andrei is completely immobilized by his dreams and nostalgic yearning for home and family which are represented by his fellow countryman Soznovsky and Domenico respectively to the point where his visions begin to transpose themselves on reality. Viewers are met with mise-en-scenes which are a carefully crafted amalgamation of real-life and miniature landscapes. The camera zooms in ever so slowly that the distinction between the two dissolves and we are left wondering what is real and what isn’t. This dissolution of what is contrived and what is natural is an extension of the previously described intercutting of the memories and dreams of Andrei and Domenico which repeatedly fractures the former’s emotions. This ruptures the barriers of circumstantial, surface-level differences and allows two cultures to interact and negotiate at a level that transcends all spatiotemporal differences.

As with the climax of Stalker, similarly, the climax of Nostalghia happens with a Andrei’s spiritual and humanist realization that he is Soznovsky as well as Domenico. The semiotics of identity have been erased only to be replaced by the randomness of deconstruction. That all these men’s dreams and desires essentially the same and are untethered to any politico-historical markers. Nostalgia transforms the initial simple understanding of home and it becomes very much like art which reshapes reality. However Tarkovsky does not cave into the comforting idea of art being a cathartic and curative form of reconciling with an unpalatable reality by reconfiguring our perspective. Rather, Tarkovsky rejects it by positing his theory that art must be paradigm-shattering and revelatory in nature which is reminiscent of the chiasmic call of Benjamin when he vindicated the work of art and attempted to imbue it with a political valence that it had lost due to industrialization and the rise of capitalism.

While Tarkovsky artistically portrayed the amorphously messy permeability of identity and memories, he juxtaposed this with the geometry of medieval monuments and arches and utilized their progressive duplication as a visual metaphor for an unending descent to madness that all three men slowly underwent. Even though the film relies on the exterior ambiance and psychological states of being, it does come to a formalistic full circle with Andrei reciting his father’s poetry as he paces about with a candle before he dies of perhaps an overdose of medication. The last shot of the film is where Andrei sits on a grassy patch behind a puddle of water with his German Shepherd and the midground is his Russian home that is overwhelmed by the sublime largeness of the Italian arches that constitute the background . There is rain and there is snow at the same time, which indicates that this is a vision that is a true amalgam of both Italy and Russia, an emotionally complex and composite reflection of Tarkovsky’s desire to return home but also his realization that he cannot go home because of the stifling mandates of the Soviet Union. With the mention of his father’s poetry Nostalghia, and the film being dedicated to his mother Tarkovsky, with great artistic poignance, revealed that his home lay within the worlds of his films.

Sequence from Nostalghia (1983) by Andrei Tarkovsky video recorded by my friend

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure

Cure (1997), directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Since October is upon all of us, and it is duly acknowledged as the spooky month of every Gregorian calendar year, I decided to inaugurate it by watching a Japanese horror film on my Criterion Channel subscription. The film in question is called Cure and directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa who doesn’t happen to be related to Akira Kurosawa in any way. While I don’t take well to horror films, I do have a penchant for Asian psychological thrillers that border on horror. Cure, from the extremely short description on Criterion Channel, looked very promising. It is a psychological thriller with elements of horror and deals with multiple murders. Did I like the film? Yes, but also no. Where would I place this film in my spectrum of disappointment and enjoyment? Somewhere in the middle. Why? I will tell you so.

The film opens with a scene of a young and beautiful woman reading the story of Bluebeard in a very spacious clinic that possibly doubles as an airy and bright laboratory. The title of the book has already set the theme of deviance. Quickly, we discover that she suffers from severe amnesia and is undergoing treatment. We learn that she is the wife of the protagonist who is a detective for a living. We soon see that the relationship of this couple is strained because of her illness despite her being a good homemaker who cleans and cooks and keeps the house running while her husband is away at work. In my understanding, it is Kurosawa’s oblique attempt at reflecting how society too looks perfectly functional and orderly while the collective malaise is hidden away so carefully that it is utterly invisibilized. Eventually, we see this trope repeated multiple times at an individual level each time a murder is “provoked”.

The seaside scenes leading up to the very first murder are perhaps the most beautiful shots the film has to offer, and that led to calibrating my expectations to a higher baseline. The long shots and the close-ups taken by Tokushô Kikumura are fantastic in terms of creating a sense of isolation and building trepidation as the camera looks over the shoulder while the victim and the instigator converse. Despite those masterful long shots, the mid-shots are nothing out of the ordinary, possibly establishing that society seemingly looks mundane—or perhaps mid-shots are not Kikumura’s strength. However, his deployment of chiaroscuro is commendable. He uses it sparingly, just enough to visually layer and even symbolize the intentions of his characters, especially the villain’s, as well as the effect of amnesia on them.

When Mamiya—the anti-hero—of the film pretends to be or really is an amnesiac and acts out his amnesia-induced behavior, his face is illuminated and his features are all discernable. He looks lost and pure with nothing remotely sinister about his intentions. The decision to cast Masato Hagiwara as Mamiya is well-served. Hagiwara’s soft and unassuming features work well to disguise the villain’s unethically curious mind and the horrors of his realizations are subtly underplayed. As he embarks to plant the seed of hypnosis into the minds of his victims, his face is cast in shadow while the face of his victim is illuminated, almost as though the latter is the sacrificial lamb with the spotlight on them. In a sense, this chiaroscuro becomes a visual representation of solipsism. That nothing in the world is truly real except the experiences of oneself. Facts and objective reality cease to exist and the suppressed id takes precedence. It is here where the mid shots work wonderfully when the camera is stationary and filming the murder of a policeman in broad daylight in the most dispassionate and matter-of-factly way. This camera handling positions the audience as voyeuristic and apathetic which, segues into the trope of society being deeply ill from within.

Naming the villain after a camera company is also an interesting decision, especially because the villain’s modus operandi is largely based on observation. He can be likened to the eye of the camera as well as the photographer. He chooses a suitable object/victim, carefully frames it with hypnotic instructions, and finally transmutes it into the subject/perpetrator of his grisly experiments. The sound design is avant-garde yet exceptional for it utilizes a disturbing drone of industrial white noise. This not only lends an atmospheric quality to the film but also reinforces a sense of verisimilitude despite being a non-diegetic soundscape and breaks the fourth wall by tricking the audience into believing that they are very much a part of this series of murder investigations. The mise-en-scène and narration until this point show great promise as we are immersed in an atmospheric psychological thriller.

Mamiya, of course, has a foil. The detective, played by Kōji Yakusho, who goes by the name Takabe, is the film’s protagonist. He is perhaps too literal and obvious a foil for Mamiya as he represents his love for order (we see how he eats his meals with meticulousness), tenacious loyalty towards his amnesiac wife who—he later admits—is a burden to him, and his persistence for justice which highlights his morally upright nature. He is also the only character who is immune to Mamiya’s hypnosis because of his unabashedly honest tirade which doubles as healthy psychological resistance in a climactic confrontation with Mamiya, as we finally witness the true depth of his character. This immunity that Takabe possesses arises from his self-acceptance that does not allow any insecurity to creep into his mind, unlike the other less fortunate victims. In a classical sense, Mamiya has finally met his match and found an unlikely intellectual companion. Takabe is an individual whom he can call his equal despite them being the antithesis of each other. The film is reminiscent of the anime series Monster where a very similar villain and hero populate the episodes.

Despite these two characters being well-defined, I do think that they were severely underutilized. The murders incited by Mamiya were repetitive and did little to add to the development and progression of the storyline. Unfortunately, this was a major section of the film. Mamiya’s lines were cyclical since he was suffering from amnesia and that took away a lot of the character’s potential. To make up for this, Takabe’s investigation of Mamiya’s rented apartment is when viewers get a horrific glimpse of his mind through the books, notes, the old phonograph playing cryptic broken sentences, and the mummified monkey tied to a pole in the bathroom. Fumie, who is Takabe’s wife, disappointingly amounts to a manic pixie dream girl whose only purpose in the film is to add layers of pathos and admiration to Takabe’s character. The opening scene of her reading Bluebeard in the clinic loses purpose and becomes increasingly devoid of any meaning as the film progresses.

Moreover, Sakuma, the psychologist who is Takabe’s friend, is created purely to serve as a vehicle of exposition. His comment about Mamiya being a missionary is cryptic, and yet, had he survived, we may have been given access to what he truly meant by his biblical remark. Perhaps it is an allusion to how he sees Mamiya as a messiah who is delivering humanity from the evils and sins it is entrenched in. Perhaps, this could be further taken as a Christian metacommentary of how the devil can enthrall man in the form of an angel or God. That is how the title “Cure” becomes an allusion to Mamiya’s twisted attempt to free society from the shackles of insecurity and Takabe’s endeavor to “cure” the sickness called Mamiya that is quite literally hollowing out society by removing him from society. This film takes a meditative turn that underpins themes of human deviance and psychology.

By this time, the film has unfolded in such a way that my judgment of it is largely dependent on the way the ending plays out. Unfortunately, the ending is rather abrupt with Takabe losing the last vestiges of his patience and killing Mamiya very abruptly when the latter is just about to open up. There is a possibility that it was done to preserve the mystery that shrouded Mamiya’s character, but I am led to believe that perhaps a suitable explanation of Mamiya’s intentions and character wasn’t realized. However, it does feel realistic enough in the sense that something utterly evil must be eliminated without the need to understand it for the sakes of one’s self-preservation and a society that rampantly feeds on and breeds insecurity. If the film had ended here, I would have been still somewhat satisfied. What really left a bad aftertaste for me was how the very last scene of Takabe telling the waitress that he is done with his dinner and thanking her and then witnessing the latter pull out a knife and about to commit yet another murder ruined the aesthetic and narrative integrity of the film by being badly shot and confusingly open-ended.

At first, I thought that perhaps it is Mamiya who had orchestrated this by anticipating his death by the hands of Takabe. That he had hypnotized her to kill Takabe with the intention of not only getting back at him but also posthumously winning the war of wits and determination. But after pondering on this narrative far too long and being increasingly agitated by the sheer maladroitness of it forced me to come up with a theory that this hypnosis that Mamiya had learned from the German physician Mesmer from the 18th century and was subjecting his victims to, is actually a kind of virus that seeks out a host to survive and transfer from one body to the other. Mamiya may have been a good host for the hypnosis-inducing virus but he still suffered from amnesia like his victims, which, in the end, made him unsuitable. Perhaps, through Mamiya, the virus was trying to migrate to a better host and Mamiya’s victims were all potential hosts.

Mamiya and the virus both recognize the resilience Takabe demonstrates. We are led to believe that Takabe truly is the saviour who kills off Mamiya. But if we were to go back to the scene where the former investigates the latter’s home and plays the gramophone in a bid to gather clues, we realize that it is this moment when the virus successfully enters Takabe. This confirms two things: that Mamiya was not strong enough to transfer the virus to Takabe, thus making a less-than-ideal host, and that Takabe is a better host than Mamiya. Takabe killing Mamiya without hesitation is his definite break from his moral scruples.

The second confirmation exclusively rests on the final scene, where Takabe admits his wife in an asylum instead of taking her for a vacation and interacting with the waitress in the restaurant. He does not need a lighter or a glass of water to hypnotize his victim, unlike Mamiya who had to rely on an external object. Takabe is not only self-sufficient with his hypnosis but also undetectable. His memory is intact, and he behaves like an upstanding citizen while hypnotizing his victims. In the end, there is no “cure”. This is what pushes the psychological thriller into the genre of horror and saves the film for me.

Despite the script’s psychological fecundity, Cure did not deliver to my expectations as it left much to be desired and decided to comfortably lodge itself as a middling film in my spectrum of good to great cinema for the reasons that I have just discussed. However, it did have its highlights and moments in terms of cinematography and mise-en-scène when it came to creating an atmospheric thriller peppered with elements of horror and alienation as the characters of Mamiya and Takabe somewhat successfully but laboriously carried the film to the end.

Cure (1997), directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa

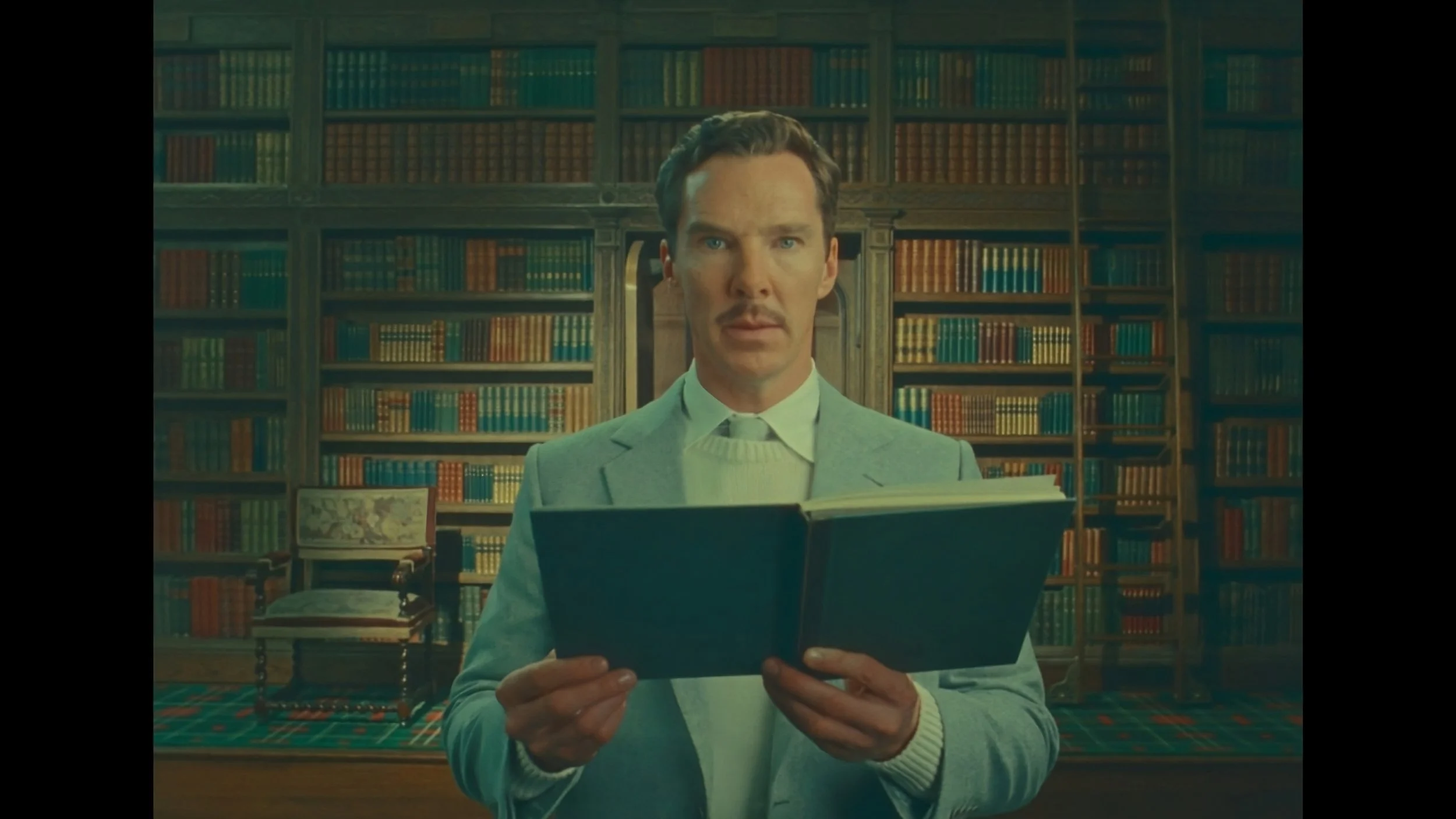

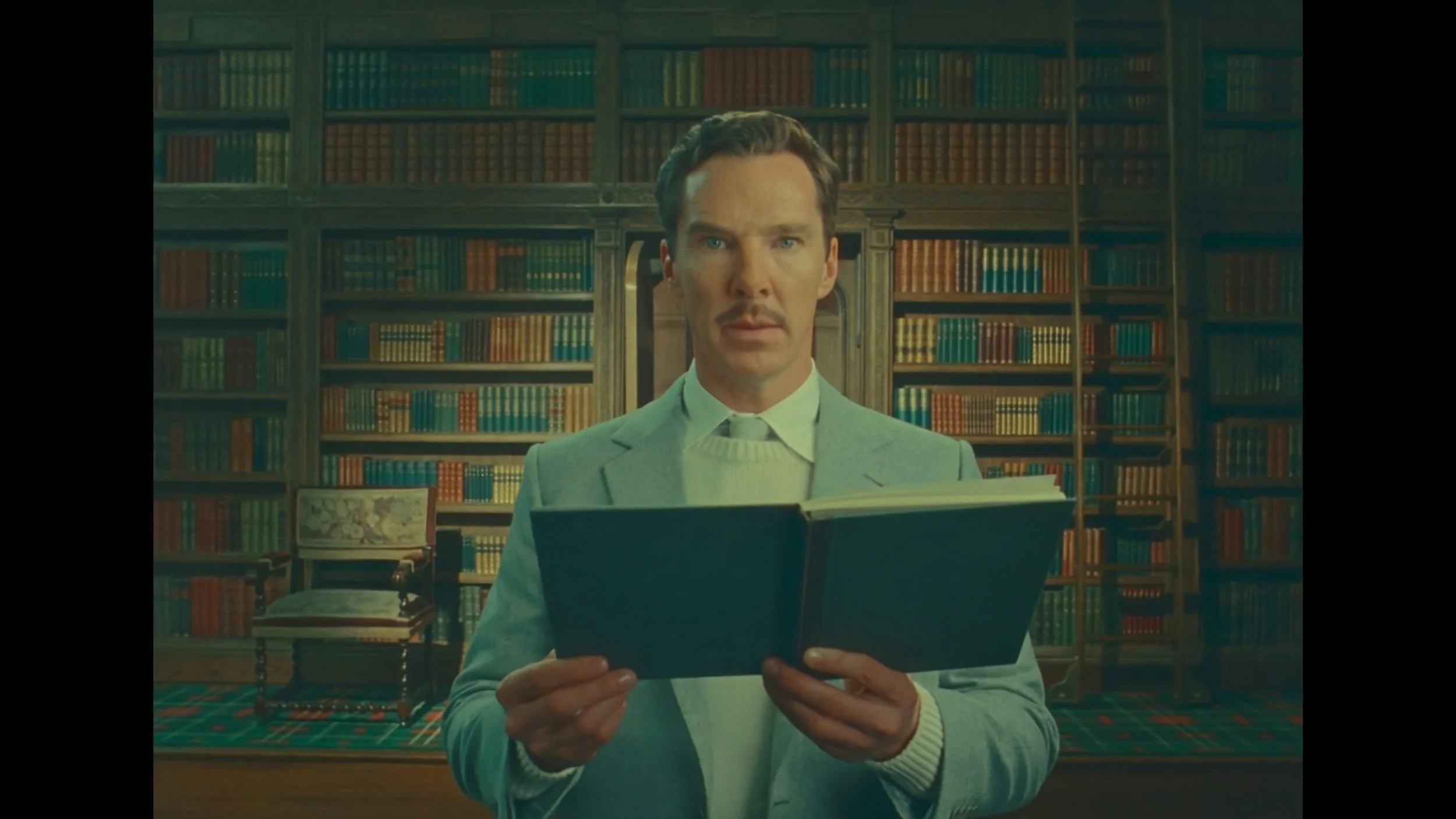

Wes Anderson’s The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar

The recently released Netflix short film The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar by Wes Anderson which comprises a spectacular cast of Benedict Cumberbatch, Ben Kingsley, Ralph Fiennes, and Dev Patel was a much-anticipated watch for me, and so, I watched it with a friend last night. For someone who grew up reading Roald Dahl’s works and loves Wes Anderson’s theater-esque sets and geometrical patterns, I had high expectations from the film but I was left feeling a little perplexed.

This is one of the works by Dahl that I haven’t read and so I went in with an open mind and enjoyed the bizarre opening of the narrator laying the groundwork for the story to proceed. The sets deployed in the film were an eclectic amalgamation of Wes Anderson’s quintessential bright and pastel color palette and The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari’s theater-like props and set design created a sense of nostalgia and history for even a casual cinema enthusiast. The film’s deliberate use of the 4:3 aspect ratio from the silent era was a good call in terms of situating the movie as one that should have perhaps been made decades ago when this particular story by Dahl came into circulation. However, in my opinion, the quirky opulence of the set warranted a modern 16:9 screen ratio. I don’t think it was a stylistic necessity because pretty much everything on the set and the costumes were evocative of a bygone era.

The narratorial voice and the dialogue in the movie at times overlapped, which I am assuming was how the story was originally written. But this overlap became somewhat of an annoyance as the film progressed despite, what I assume, is Anderson’s attempt to remain as authentic as possible to the story. What I did like about the film was that some of the actors played multiple roles and there were stagehands in almost every scene moving around the props and replacing them as the scenes progressed, and the actors at times addressed the viewers by squarely staring at the camera that was filming them as it creatively deployed the technique of the metatheater within a film. However, this begs the question: what conventions, tropes, and limitations of theater or cinema is Anderson trying to explore? If there was some kind of theoretical dissection/deconstruction that he was attempting through this cinematic piece, it has sadly not been delivered.

While the concept of mixing theater and cinema has been done before, the use of sound does make The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar stand apart as an avant-garde film even if it is kitschy in essence. In our current times, where there is an abundance of innovation in terms of cinema techniques, this may not be the most novel take by an auteur, but it does possess an undeniable charm and has subsequently carved a place of its own in terms of wedding the old and the new in cinema, and blending theater and cinema into a visually cohesive experience.

My issue becomes more serious as a viewer when it comes to the pace of the movie. It does go by rather quickly and there are many moments when the scenes feel rushed. It is almost as though Anderson wanted to wrap up the film within an hour—which he did in just under 40 minutes. But it came at the cost of not being able to flesh out certain scenes, especially where the doctors are meticulously blindfolding Khan and the meditation process imparted by the Indian yogi. Most of all, Henry’s character came out rather two-dimensional because a jarring paucity of time was given to Henry realizing the greed of the people in the casino and how he came to the decision of fashioning himself as a master of disguise cum anonymous philanthropist.

Of course, the film does have the unique energy that all films by Anderson usually possess. Nevertheless, it left me wanting more and not entirely satisfied once the film ended. The urge to keep this film in the realm of a short film heavily compromised the very essence of “humanity” that is the leitmotif of all of Dahl’s works as the film felt more like a fantastical yet amusing, anecdotal reportage than a visual story deliciously unfolding. “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar”, the short story had the potential to shine as a feature film rather than be retold in a way that overwhelmingly focused on keeping the formalism of both the literary work and the cinema in conjunction. Here, Anderson unfortunately is ironically foiled by his obsession as a formalist auteur who tirelessly pushes his artistic expression to create his trademark films of geometrically patterned colorful sets and metatheater-esque techniques.

Cold Touch Versus Warm Touch Film-makers

Above: Oppenheimer by Christopher Nolan; Below: Stalker by Andrei Tarkovsky

Just a couple of days ago, I finally got around to watching Oppenheimer by Christopher Nolan in the theater albeit not on IMAX (which was such a shame as it was shot on IMAX cameras and I have always preferred watching cinema on IMAX or on my home theater projector), and I was struck by differences that set great filmmakers apart from each other. Though there is no official way of distinguishing them as two distinct parties, my mind has already categorized them informally as Cold Touch and Warm Touch directors.

To me, directors like Stanley Kubrick and Christopher Nolan, are cold-touch directors. They focus on the macrocosm more which often leads to working with the surroundings extensively and they sometimes deliberately make the surroundings grand because it is easier that way to make an impact. Multiple, complex ideas are woven together, almost like a Hans Zimmer soundtrack that leaves the viewers awestruck. In other words, these directors choose to demonstrate the sublime through a careful collaboration of screenplay and cinematography. Their world is vastly exterior though they do have many moments that expose a character’s inner landscape.

But Andrei Tarkovsky approaches his shots from an interiority. The relation of the camera is one with or at least intimate with the character’s mind’s eye. In a sense, Tarkovsky superimposes human perception and psyche in his shots and this superimposition is melded so seamlessly that it becomes an inextricable part of the viewer’s visual experience. He picks on the ordinary and transforms them into poetry. Tarkovsky’s shots will make you cry while Nolan’s and Kubrick’s shots will leave you breathless as their films are more event-oriented whereas Tarkovsky’s are single event odyssey much like a symphony of beautiful visual notes artfully strung together. By now, it is obvious that I am biased towards my beloved Tarkovsky despite my great love and admiration for the other two aforementioned directors.

I’ve probably done a terrible job at differentiating and wording out the feel I get from these directors. But it is 3:52 am and I have been suffering from a stiff neck for over 16 hours, so my mental faculties are at their limit and I should be forgiven. Cold touch and warm touch are not limited to the superficialities of color tonalities or the approach of the directors towards their subject or goal. Truth be told, I don’t think that there are any words to describe the differences. These can only be felt as they are deep enough to be obvious to our sensory and cerebral perceptions and elusive enough to evade being captured by the limitations of vocabulary.