Review: On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

Negotiating Freedom & Building a Fragile World With Silent Tenderness

‘I fear the knowledge will dissolve, will not, despite my writing it, stay real…just as I don’t know what to call you—White, Asian, orphan, American, mother?” p. 63.

I had taken a course on Asian North American refugee narratives in 2019 when Ocean Vuong’s very first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous was released. This book instantly became one of my all-time favorites, and now that I am writing this piece, I have come to love it more than ever. Vuong’s prose is poetic and luminescent and always full of honest feeling. For someone like me, who has always been misidentified in terms of race and nationality both in my home country and abroad, the story resonated with me and yet, there was so much more that I received from this novel. Most importantly, the book showed me that building a world for one who was displaced in multiple ways in the world, was an act of tenderness, defiance, and relentless perseverance in the face of fate. Geography is destiny.

This review that I have penned isn’t a typical book review. It’s actually a reflection of the parts that struck me as I read the novel, so it follows a meandering trajectory. I will be focusing on language which is the currency of any kind of social elevation in a foreign country, and how the lack of mastery in it reduces the individual to a life of limited existence in the peripheries of society. Language is a fundamental form of creativity or creation. It is how we encode our personalities into assimilable, verbal bits for the world to understand us; to help them recognize us the way we want to be seen and acknowledged.

The protagonist, who goes by the name Little Dog, wonders why the language for creativity cannot be the language of regeneration as well. The sense of loss is already prevalent when he ponders on this thought. It is ironic that as a writer, he is unsure of what a writer is supposed to be and do. As a child, he practiced ascribing different meanings to words to protect his loved ones. Expletives painted in red by strangers on the door of his home were transformed into Christmas greetings while dresses that his mother chose for herself became fireproof. It is similar to his mother’s flight of fancy but is much more nuanced and complex because he does not do away with words completely. Rather, he removes the conventional meaning accorded to each word and invests each word with new meanings drawn from his personal philosophy. It is an attempt at regeneration but not quite so. He systematically demonstrates violence towards the seemingly neat Saussurean signifier-signified dyad. But language keeps on failing him time and again, and by extension society and the world at large. These are his first acts of rebellion.

In his late teens, however, he finds a kind of solace when he begins working in the tobacco harvesting barn. The fracture in his identity caused by his mother’s hybridity and his mystery grandfather is sutured through teamwork in a barn with his Spanish colleagues. It is a space for the excluded to feel like a family in the loosest sense of the term and accept each other’s differences. He discovers different ways to communicate and thus renders verbal language useless. It is here, for the first time, in this unconventionally written bildungsroman, that the act of performance takes precedence over enunciation. Little Dog, for the first time ever, consciously uses his body/gestures to communicate. This was the freedom that was allowed and accorded to everyone in the barn as it was birthed by the lack of a common language amongst his colleagues and him. This space for the collective outcasts is also where he meets his first love, Trevor.

This barn marks the beginning of Little Dog’s lifelong struggle to break out of the written and spoken word of the world, reanimate those words with new meanings, and use his body to communicate that which cannot be achieved through mere words. Language, to him, is alienating precisely because it is so slippery, inadequate, and inconvenient; bound up with rules of syntax and semantics, that he fears it will pathologize his pure and wordless emotions and detach them from his being. Just like snowfall that covers everything that is distinguishable and based on differences dependent on sight and name, Little Dog too, deliberately fills up words with his own meanings, thus erasing all former distinctions of the langue.

This struggle gains further impetus and authenticity when, right after showering, he sees himself in the mirror (p.108). This is his long-awaited initiation into the Lacanian Mirror stage. He is finally able to see himself as a whole being, without any flaws, beautiful enough to demand the right to live unencumbered. He thinks of the monarch butterflies and juxtaposes them with the ill-fated buffaloes rushing to their deaths. He realizes the need to defy gravity—that, which is an insurmountable law of nature. It is this defiance of gravity and redesignating a urinal as “Fountain” by Duchamp that made both works of art. This systemic violence done by the act of defying gravity, a universal, unalterable rule shared in not just the image-sound dyad but also within the image itself, is what Little Dog believes to be true freedom. To defy nature, to defy destiny—seemingly at the cost of one’s life, is to live out true freedom, at least in this world. In this world where his kind and he were like buffaloes rushing to their deaths, he wanted to be like the monarch butterflies that could glide through life, over precipices, with beauty…because he believed that every life in this world was gorgeous, even if for a moment.

There is also a motif of fakeness or imitation—the creation of an illusion to make this life bearable, which runs throughout the novel: e.g., Paul not being his real grandfather, American tobacco being fake, the pink peaches painting in Trevor’s mobile home being fake, and even Little Dog’s first act of having sex being a hand-induced stimulus. All these things are revealed to be fake when Little Dog encounters them at close quarters. Realizing that very few things in life are real and palatable, he is inclined to look at things from a distance because then things are not defined enough to reveal themselves and there still exists a place pregnant with possibilities. The closer one gets, the more vulnerable one becomes, not only because of inevitably eliminating those possibilities that perhaps never even had a chance to materialize but also because of risking the internalization of rules that govern spaces that have already been defined by the world. Rules are like relics but divested of their ritual significance. They are static and fascist in their core, thus leaving little or no space for negotiation. Similarly, city life and city roads are entrapments like words. To define is to limit and curtail. The tobacco farm field and the field underneath the city grid are all free of demarcations. These are spaces of boundless possibilities where rules don’t apply or are largely invisible. Rules in the world are a form of communication and order, but in these spaces, words are supplanted by gestures—thus eliminating the necessity of rules and opening up spaces of negotiation and creation.

However, Little Dog is still a part of the world despite his marginalized identity as a second-generation Asian American, and the world is built and functions solely on communication. Little Dog feels this very acutely because of his queer identity. He realizes the inadequacies of both Vietnamese and French languages when mirroring lived reality with words. He states that there is no word in Vietnamese for being queer, and in French, queer bodies are defined by a criminal word. However, Little Dog exists and he is not a criminal. He thus grapples with language again when he tries to explain his identity and queer desires to his mother. Does he even exist since he has no way of telling the world what he is? Similarly, when Lan, his grandmother, is diagnosed with cancer, Little Dog and his mother try to explain her predicament to her and once again fail. Since life is so complex and fantastical with its repertoire of phenomena, human language which is meant to pigeonhole and compartmentalize incidents and their respective causes, fails deplorably in meeting this objective. Here, science and medicine become witchcraft because language once again fails to even adequately mirror the realities of life. After all, language is a heuristic byproduct of culture and lived-out social realities.

Little Dog increasingly depends on the language of the body now. He remembers the gestures of his hands and legs as well as those of Lan when they used to knead his mother’s tired body soon after her return from the nail salon. These gestures become a language expressive of love and representative of the concept of a family. He wonders why people still name flowers when flowers themselves are so ephemeral. Does Little Dog see himself as a flower since they are so transient? What makes humans name things in their painfully brief lives? Perhaps naming things situates us somewhere in the narrative of the world, but in Little Dog’s case, his identity eludes such simple, neat compartmentalizations. This is why he constantly rebels against language and the structures and rules that exist as a consequence.

However, Little Dog knows that he cannot be free of language. When he was born, he was languaged into existence. He was already considered a healthy, “normal” boy even before he learned to speak. The freedom he is constantly searching for throughout the narrative—the elusive “something” that he keeps mentioning—is the concept of freedom that can never be actualized and transformed from being a noun to becoming a verb no matter how tenaciously and hopelessly he practices it. And so, he provides a response through utterance which essentially reiterates the names of all those people who ask him the question, “Where am I?” Through this utterance, he conflates the identities of these individuals, such as his mother and Trevor, who are marked by culture, history, and race, with space. Through this inquiry, he situates them in an imaginary space, much like his mother’s coloring books, his rainbow-colored cow from grade school—full of possibilities where the very act of identifying them also liberates them. It is an ironic and deeply poignant act with which he creates by virtue of answering their questions with a clear enunciation of their names, hopeful, imaginary spaces where everyone and everything is “good”—the Utopia, Little Dog’s Utopia. He builds a place that conflates his mother’s “Everything good is somewhere else, baby. I’m telling you.” (p. 55) with Trevor’s reclamation of Little Dog’s beauty, “Good as always.” (p.206.)

Little Dog’s notion of beauty throughout On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous was a two-pronged approach. He defied the world not only by the very act of living but also by the violence he consistently did to langue, which he constantly replicated, thereby extending it into space and time. His search was one that would never end because he was constructing a world as fragile and precarious as words.

Bibliography:

Vuong, Ocean. On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous. Penguin Press, 2019.

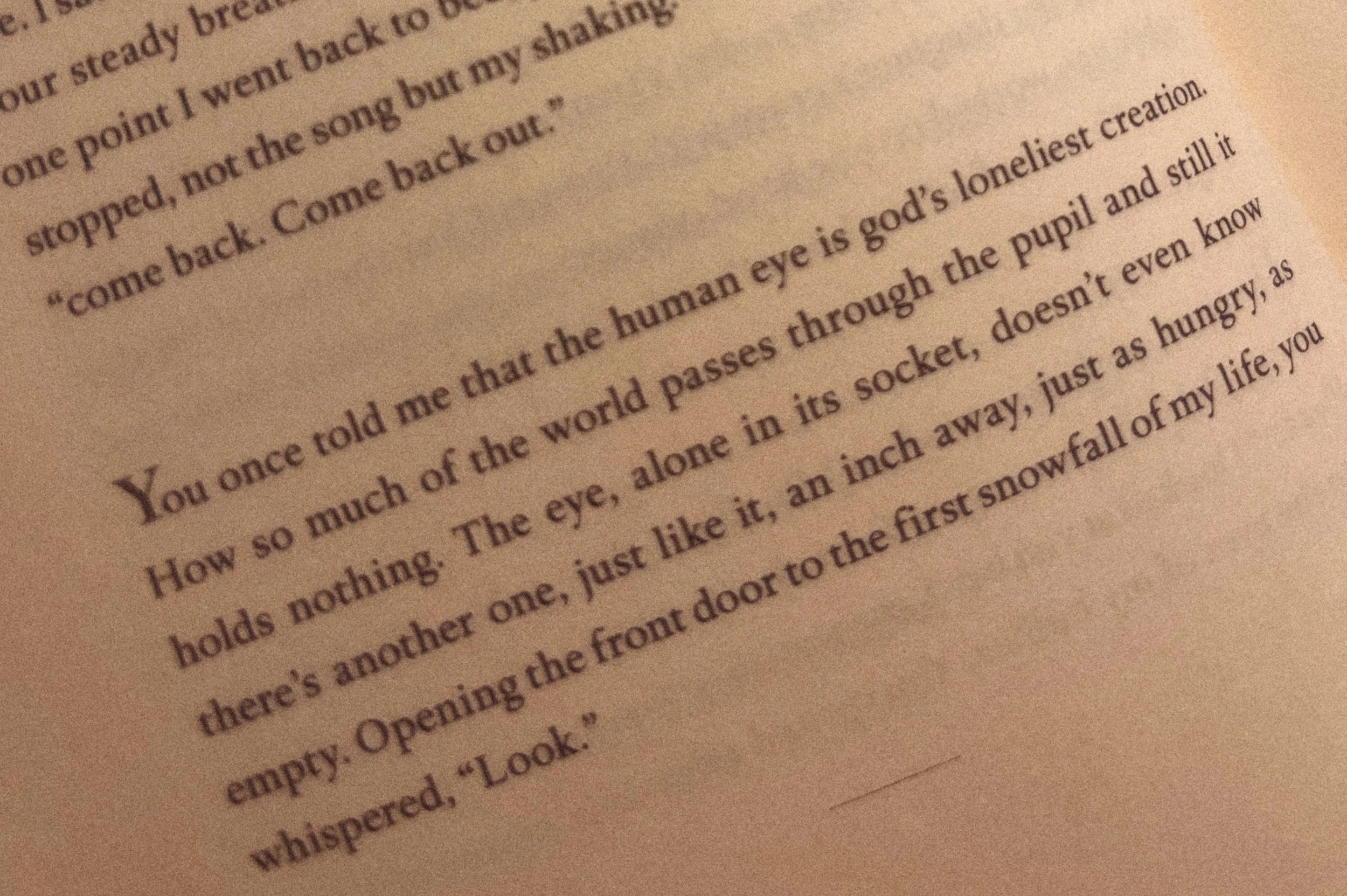

an excerpt from page 12 of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong