home as heterotopia: understanding Do Ho Suh’s “Home Within Home”

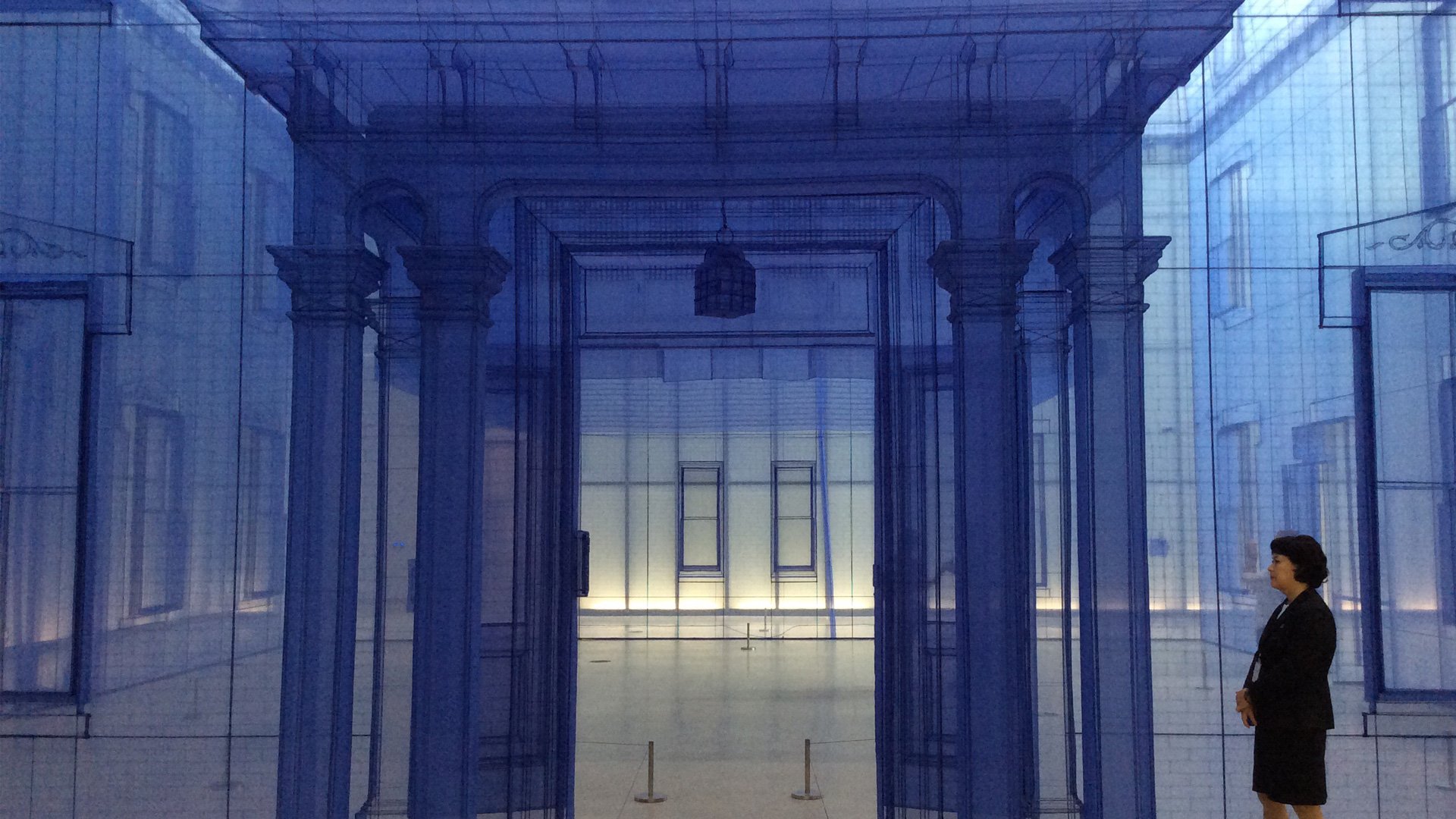

Home Within Home at MMCA

When I began to conceptualize the chapters that would collectively constitute my dissertation, I came across Do Ho Suh and his phenomenal fabric sculptures. The photographs I saw online were mesmeric and I immediately knew that this particular series titled Home Within Home Within Home Within Home Within Home (2013) would be a fabulous addition to my research that primarily deals with literature and the visual arts. Home Within Home delicately balances paradoxes in the most delightfully visual way. The sculptures are light and ambient, but at the same time, dense and opaque, depending on the distance between them and the viewers.

That Do Ho Suh played on the concept of what home truly is, was a very intriguing question for someone like me who had lived a fairly nomadic life, changing places every few years and experiencing the sensation of being uprooted and subsequently rooting myself in new places—only to leave for another place. The more I observed these ethereal sculptures, the more I thought of how this series embodied the triadic structure of a thesis, an antithesis, and a synthesis that are integral to Kantian dialectics. I was fascinated when I suddenly associated the walls of a “home” with the largest human organ, the skin, both of which are important media through which one experiences and distinguishes between phenomena (the world as we experience it) and noumena (the world as it is in itself) when engaging in philosophical speculation.

As I went down my art-inspired cultural theory rabbit hole, I began to quickly make associations between home as heterotopia. We always considered places like gardens, brothels, museums, prisons, etc. as spaces that were interesting in terms of mapping out their relationships with each other and their physical location and organization within a society, but we never really considered our homes to be one such site of exciting exploration. Home was too prosaic and too familiar to offer such kind of excitement. But this, this was a heterotopia within the museum—which was another heterotopia. This heterotopia within heterotopia series inspired me to write this post wherein I wax lyrical about it without sounding too academic and hopefully less opaque.

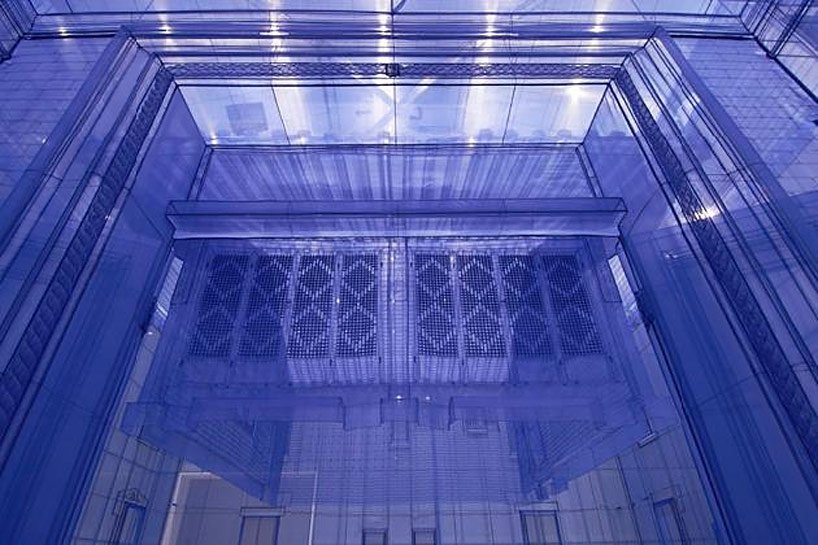

Home Within Home by Do Ho Suh is an art form that would immediately stop a viewer in their tracks and inspire awe. From the photos, I could tell that seeing the installations in person would be an immersive experience. What strikes the viewer immediately is the sheer enormity of the installation. A true-to-size rendition of a townhouse occupies the exhibition space. Moreover, this diaphanous 3-D rendition is completely made of silk threads and is the exact replication of the exterior of Suh’s Rhode Island address. The installation visually speaks of a space that Suh inhabited. It was his first “home” away from home.

“The idea of home as a space, a physically delineated, geographically locatable place, is perhaps the most common way of reading home.” – Helen Taylor, pg. 21, Refugees and the Meaning of Home

Whenever we think of “home”, we relate a particular place to the relationship we have with it in purely spatial terms. Home thus becomes a place of dwelling. The act of dwelling includes regular rhythms of life that mark this space such as daily routines, celebrations of birthdays, and other notable events that happen in a cyclical manner rather than just linear incidents. In other words, the intersection of temporality and spatiality of a space is a pivotal attribute of a specific space that we call home. However, because habits are intrinsic to humans, this particular attribute of a home can be carried over. In that sense, home becomes mobile.

Home as a reflection of and carapace for our personalities:

The material used in this installation is an interesting choice. Made completely of silk threads, this intricately detailed installation appears to be more of a semi-apparition than anything else. It is as though the concept of “home”, as we instinctively understand it, has been given a shape and has become palpable. Silk being the preferred material for the construction of this townhouse indicates the idea that home is an organic, semi-living space that protects us from the outside world while nurturing us from within. The usage of silk has a dyadic purpose. It is also a natural fiber that is woven into clothes that are used to protect our body while also defining our personalities to an extent. However, Suh has mixed these two characteristics as though they were different elements of the Periodic Table and concocted an entirely new compound that has retained the properties of its parent elements. In this case, one can see through the delicate exterior but passing through it may not be so easy. Suh has crafted this work using traditional Korean sewing techniques combined with 3-D modeling and mapping technologies that have enabled him to bring this “ghost” to “life”.

The use of silk threads and the construction of a home using a material that we have used for centuries begot me to wonder why textile was the chosen material for this ethereal sculpture. The simplest correlation that I could make is that just the way a home protects and encases us from the world outside, clothes too follow the same principles of functionality. Just as clothes define the nuances of our identity, our home is also a reflection of our identity.

Home as a product of meditative performance:

Sewing is a technique that is dependent on the motion of repetition that is both meditative and trance-like. When one sews long enough, a piece of cloth is created. In that sense, I likened the regular rhythms of our daily life encompassed within a space of habitation to the threads that have gone into making Suh’s art installation. If I were to take this analogy further, it would mean that home is not a fixed product but rather a product of performance which can be best understood as being in a state of constant reimagining and practice. As we perpetuate old habits, we acquire new ones perhaps from various channels of our life and sometimes a few habits run their final course. Over time, these habits with their repetition transform us. Our identities thus undergo changes and revisions along with the space in which they take place.

Beyond these sweeping similarities of clothes and homes, the intention of leaving the interior of the Rhode Island townhouse empty save for yet another house is one that lead me to wonder why Suh decided to quite literally put a home within a home. The interior of the townhouse does not reflect household furniture or appliances. Instead, interestingly, encased within this diaphanous townhouse is a smaller house made of the same material which happens to be the traditional Korean house where Suh was raised as a child.

What is “space”?

To unpack this, one would need to unpack and understand what “space” means in a cultural context. A space can exist in the world, but it only acquires meaning when it is used over time. Therefore, space has an inextricable relationship with time as it is not devoid of history. If we were to look around us, we can identify several different spaces such as sacred spaces like temples, public places like parks and shopping complexes, and private spaces like our homes. These various spaces come together in opposition and interconnection to constitute a space of localization. Evidently, we are not living in a homogenous space but spaces that are laden with qualities that are controlled and perpetuated by an unspoken and universal sacralization. In the 21st century, we are in a world where space is presented to us in the form of different as well as multiple relations with one another. According to Foucault, these relations between locations in space which are the constitutive principle of space perception are called “emplacements.”

Home as a living archive

I realize that my thoughts about “home” are sprawling out of itself so I’ll go back to the concept of home in a more hermeneutic sense. Home happens to be the most private place that one can think of. It is the space in which we dwell, where we grow older and experience the imperceptible erosion of our life and the subsequent sedimentation of our history. It is a space that protects us from the rest of the world but also connects us to the rest of the world. It is subsequently a special place with special qualities. Such spaces that can juxtapose in a single real place several emplacements that are incompatible are what Foucault called, heterotopias. Home is such a heterotopia and Suh engages us with these intangible concepts in a very material and visually pleasing metaphor of his installation.

Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that isolates them and makes them penetrable at the same time. That system can be a ritual that one must perform before entering a temple or perhaps something as prosaic as turning in a key to access the space. The latter is how homes are usually accessed. Our home not only is our haven, but it also contains artifacts from the outside world and the various lives we lead in other spaces that we occupy once we step outside of our home, be it items related to work, an excursion, a memorable incident, etc. These come together to become an eclectic assortment of identities that constitute us.

Home thus becomes a personal museum that is constitutive of both our memories and our present. Suh represents this concept of home as a heterotopia by constructing his childhood home within the permeable walls of his Rhode Island townhouse. A traditional Korean home is suspended from the ceiling, within the Rhode Island townhouse, floating like yet another ghost, partially visible through the multi-layered panels of silk. He shows, through the silk threads, the permeability of identity and how it accumulates different facets over time which are visible and distinguishable in a manner that is similar to viewing the suspended traditional Korean house from outside the Western townhouse in his installation.

Home as a Kantian synthesis of being and becoming

Now that I have sufficiently established that home is not a fixed product or entity that is rooted in a particular place but a summation of routines that we construct or let fall into disuse, home also becomes a special, paradoxical heterotopia where there is constant negotiation. It is the site where we bring in new elements from the outside world and periodically discard the old. We witness Suh’s American abode has subsumed his Korean home and all the memories associated with it without obliterating its distinct characteristics. Through this, Suh visually translates the concept of an ever-expanding, ever-changing space that we call home.

These two homes, one within the other also made me wonder about the creation and sedimentation of personal identity. I would like to think it’s the gradual layers of nacre that ensconce a grain of sand in an oyster but this metaphor is too beautiful and perhaps a little simplistic for Suh’s work. After all, personal identity is not something significantly material like clothes being worn but deals primarily with the experiences that we have undergone in our lives and the ones that we are yet to experience.

Home is a rhizomatic structure of memories

I also wondered why Suh chose silk threads instead of an already woven silk fabric. Of course, the obvious answer would be because threads offer translucency whereas a woven fabric would usually offer opacity. But then, threads when put together without weaving form a dense network of connections with other threads that go into making the whole structure of the Korean house as well as the townhouse. There is no origin and there is no center. This dense network of silk threads acquires a rhizomatic form wherein these lines of threads become two-dimensional extensions spreading in all directions to form the containers for temporal manifestations of home; in this case, these are the Korean house and the Rhode Island townhouse.

Each thread exists independently which is akin to how memories also exist in Henri Bergson’s understanding of the past. Past events exist as a separate bloc. When we recall a past incident, we don't replay the events in a sequential manner. Rather, we go straight to the memory and recall it. Thus, the past is non-linear and becomes a condition for the existence of the present. Quite obviously, the past is a prerequisite for the present. This indicates that our identity is something that has determinacy only when it is read retroactively. In other words, our identity which remains largely stable is also constantly growing as we live through every day and forge new connections or maintain or severe old ones. Just as the threads come together to form the textile monument, memories too come together to create our identity. And just as silk threads change with time and wear out and morph, memories too are extremely delicate and malleable with respect to the linear flow of objective time.

In this sense, the past is a condition for the actualization of the present connects with the privileging of becoming over being. Being is merely a momentary, subsidiary, and largely illusory suspension of becoming, according to this view. Becoming is always the primary fundamental. The determination of every actual being by the virtual past in its entirety remains contingent. It only has determinacy when read retroactively. Becoming is a process, and in this case, Suh’s identity acquires a new connection—that of his American home and culture. And so, playing by the rules of retroactive determinacy, Home Within Home can be viewed in an inverse way—from within the Korean house that has made connections with the bigger townhouse as Suh has grown older and traveled geographical distances.

It is truly remarkable that simply viewing this exhibition online offered me an intimate understanding of the anatomy of home and identity formation. Suh’s artistic vision that birthed this exhibition is one that is rare and philosophically fertile. Home Within Home is a captivating series that inspired me to visualize so many cultural theories that I could only imagine in different objects and ordinary structures around me. To discover all of them in such a glorious series was a visual and cerebral delight. Do Ho Suh has indisputably joined the ranks of my favorite artists of all time.

Do Ho Suh’s installation at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) Image Credit: Cranium Contemporary