Wes Anderson’s The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar

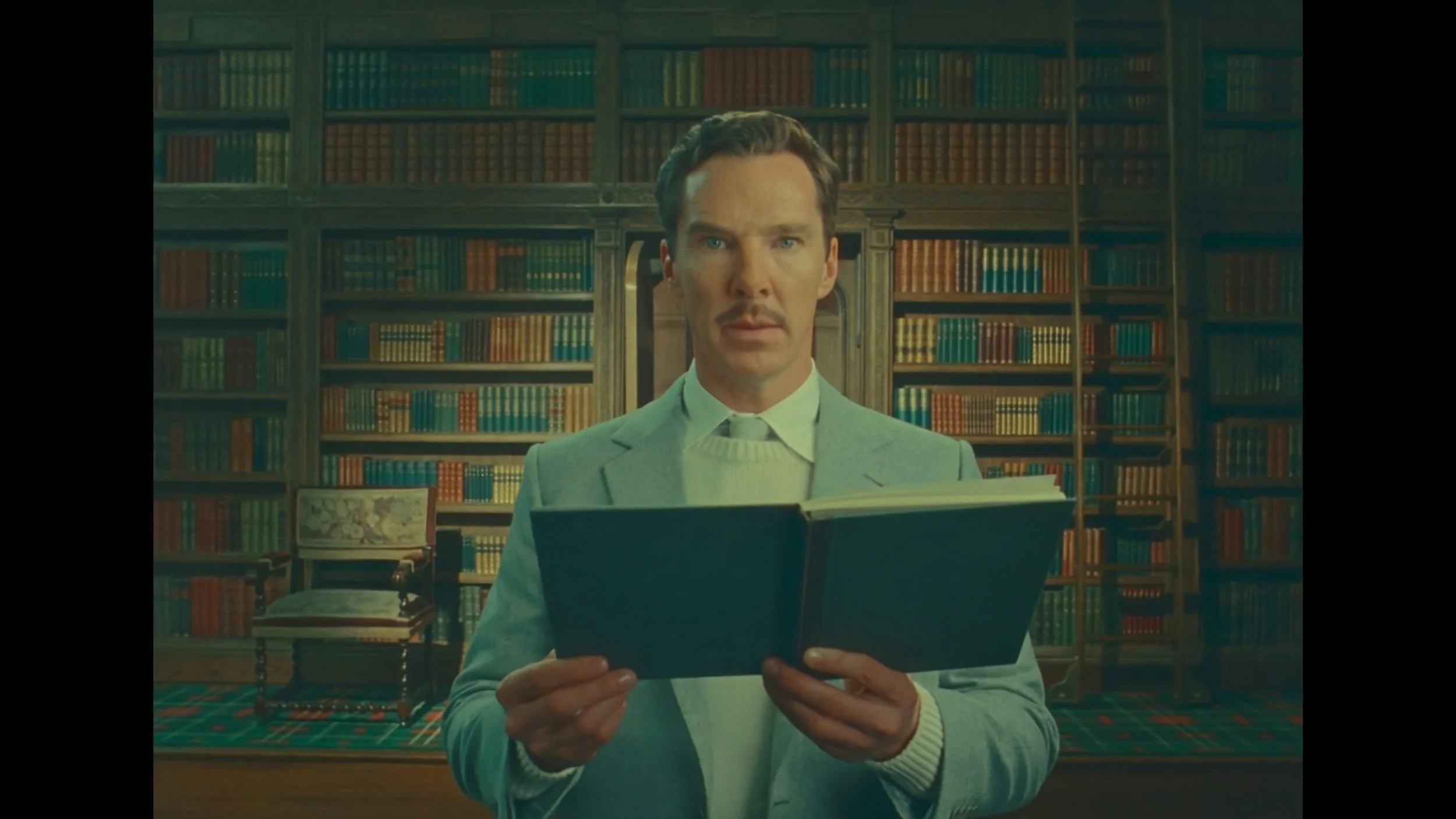

The recently released Netflix short film The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar by Wes Anderson which comprises a spectacular cast of Benedict Cumberbatch, Ben Kingsley, Ralph Fiennes, and Dev Patel was a much-anticipated watch for me, and so, I watched it with a friend last night. For someone who grew up reading Roald Dahl’s works and loves Wes Anderson’s theater-esque sets and geometrical patterns, I had high expectations from the film but I was left feeling a little perplexed.

This is one of the works by Dahl that I haven’t read and so I went in with an open mind and enjoyed the bizarre opening of the narrator laying the groundwork for the story to proceed. The sets deployed in the film were an eclectic amalgamation of Wes Anderson’s quintessential bright and pastel color palette and The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari’s theater-like props and set design created a sense of nostalgia and history for even a casual cinema enthusiast. The film’s deliberate use of the 4:3 aspect ratio from the silent era was a good call in terms of situating the movie as one that should have perhaps been made decades ago when this particular story by Dahl came into circulation. However, in my opinion, the quirky opulence of the set warranted a modern 16:9 screen ratio. I don’t think it was a stylistic necessity because pretty much everything on the set and the costumes were evocative of a bygone era.

The narratorial voice and the dialogue in the movie at times overlapped, which I am assuming was how the story was originally written. But this overlap became somewhat of an annoyance as the film progressed despite, what I assume, is Anderson’s attempt to remain as authentic as possible to the story. What I did like about the film was that some of the actors played multiple roles and there were stagehands in almost every scene moving around the props and replacing them as the scenes progressed, and the actors at times addressed the viewers by squarely staring at the camera that was filming them as it creatively deployed the technique of the metatheater within a film. However, this begs the question: what conventions, tropes, and limitations of theater or cinema is Anderson trying to explore? If there was some kind of theoretical dissection/deconstruction that he was attempting through this cinematic piece, it has sadly not been delivered.

While the concept of mixing theater and cinema has been done before, the use of sound does make The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar stand apart as an avant-garde film even if it is kitschy in essence. In our current times, where there is an abundance of innovation in terms of cinema techniques, this may not be the most novel take by an auteur, but it does possess an undeniable charm and has subsequently carved a place of its own in terms of wedding the old and the new in cinema, and blending theater and cinema into a visually cohesive experience.

My issue becomes more serious as a viewer when it comes to the pace of the movie. It does go by rather quickly and there are many moments when the scenes feel rushed. It is almost as though Anderson wanted to wrap up the film within an hour—which he did in just under 40 minutes. But it came at the cost of not being able to flesh out certain scenes, especially where the doctors are meticulously blindfolding Khan and the meditation process imparted by the Indian yogi. Most of all, Henry’s character came out rather two-dimensional because a jarring paucity of time was given to Henry realizing the greed of the people in the casino and how he came to the decision of fashioning himself as a master of disguise cum anonymous philanthropist.

Of course, the film does have the unique energy that all films by Anderson usually possess. Nevertheless, it left me wanting more and not entirely satisfied once the film ended. The urge to keep this film in the realm of a short film heavily compromised the very essence of “humanity” that is the leitmotif of all of Dahl’s works as the film felt more like a fantastical yet amusing, anecdotal reportage than a visual story deliciously unfolding. “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar”, the short story had the potential to shine as a feature film rather than be retold in a way that overwhelmingly focused on keeping the formalism of both the literary work and the cinema in conjunction. Here, Anderson unfortunately is ironically foiled by his obsession as a formalist auteur who tirelessly pushes his artistic expression to create his trademark films of geometrically patterned colorful sets and metatheater-esque techniques.